by Kee-Lou Ooyman

The city of Istanbul is surrounded by water. Some of today’s most iconic images include the constant ferries between the European and Asian side, and fishermen at the Galata bridge. The historical peninsula (now Fatih) is flanked by the Golden Horn to the north, the Bosphorus to the east, and the Sea of Marmara to the south. Nonetheless, throughout its entire history, water has been the main concern for this important city that was known as Byzantion, Constantinople and now Istanbul. All earlier mentioned water sources are salted water, and therefore not drinkable. Instead, Istanbul has been importing drinkable water from outside the city for more than a thousand years. The availability of fresh water was dependent on the number of people that had to be supplied, the available water infrastructure, but also more unpredictable aspects such as war, disease and droughts.

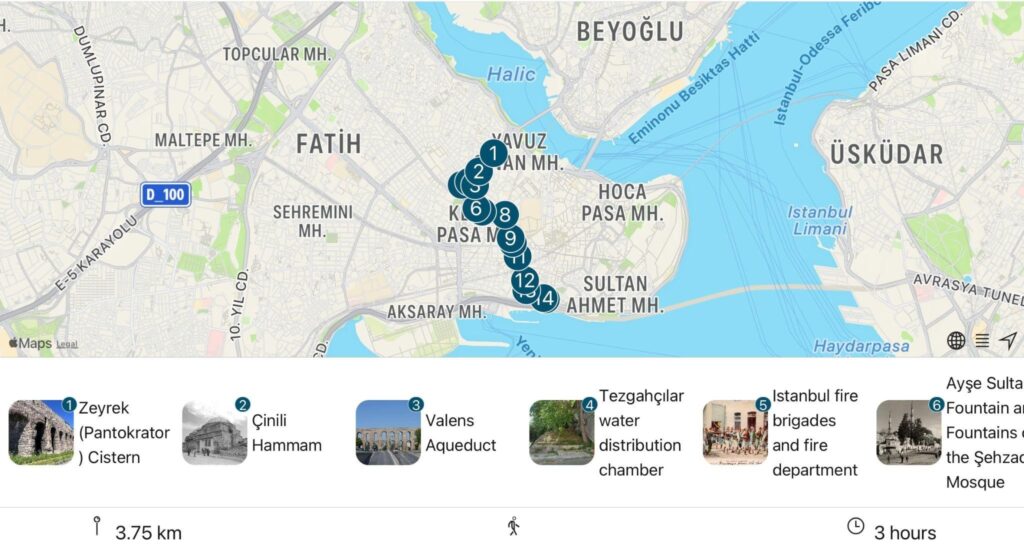

How did Istanbul deal with these water problems? What waterworks can you still see in the city today? Why is Istanbul’s water heritage still relevant today? These questions formed the drive behind the creation of the Water Heritage tour in the KarDes-app.

Climate change: a challenge to the water supply

The problem of Istanbul’s water supply is not merely historical. On the contrary, the problem of supplying 16 million people daily with drinkable water is still a very relevant one. The increasing population of Istanbul and the rise of temperatures during summer strain the modern water supply. The scarcity of water has been highlighted by municipal authorities, and even made the news in 2023 (see above). But we are not the first ones dealing with this problem: for thousands of years, Romans, Byzantines and Ottomans faced the same problem of scarcity and drought, and they left traces of their efforts to supply the city with freshwater.

The Water Heritage tour, which was developed in collaboration with the Hrant Dink Foundation as part of KarDes’ multicultural heritage tours, aims to highlight these traces. They are not always clearly visible, but they come in all shapes and sizes. A keen observator will notice both the gigantic arches of an aqueduct bridge, as well as the half-hidden roof of a water distribution chamber. The tour starts in the heart of Fatih near Zeyrek mosque, and runs all the way to the coast of Kumkapı harbour. On the way, you will encounter all sorts of water-related heritage, which all fit in the long history of Istanbul.

An (un)strategically placed capital?

It seems a bit odd that the capital of two world empires – the Roman/Byzantine and Ottoman Empire – was situated on such a seemingly disadvantageous spot. Why was one of the most significant cities in history founded on a location that lacked freshwater?

Istanbul was originally known as a small Greek colony called Byzantion. It was not particularly significant, but prosperous. For this reason, the emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138) already built a system to supply it. It bore the name of the emperor: the Hadrian Waterway, which imported water from the Belgrade Forest to the eastern part of Fatih (now around Topkapı). It was sufficient enough to supply the small area where people had settled; for this reason, the channel followed the lower slopes alongside the coast. Water supply systems such as the Hadrian Waterway entirely relied on gravity to carry the water into the city, so the engineers needed to adjust the route according to the landscape’s relief and properties.

Byzantion entered the world stage as Constantine the Great (r. 306-337) chose this spot to found his new capital city in 330 CE: Konstantinopolis – the City of Constantine, also known as New Rome. Strategically, it made sense: Old Rome in Italy was hard to defend, and too far away from the borders to respond adequately to threats of invasion. Constantinople lay closer to the wealthy east, and since it was surrounded by water, was easier to defend and more accessible in terms of communication. To make Constantinople a worthy capital, Constantine started to import building materials, monuments and people into his new city. The city was artificially enlarged. With the rapid increase of the population, people started settling further towards the hills to the west. The water infrastructure of the small colony of Byzantion was not equipped to provide fresh water to a metropolis: it both lacked the capacity, extensions, and reach to do so.

From Valens to Mimar Sinan

And so, Constantine’s city would struggle to provide its inhabitants with basic necessities such as drinkable water. Simultaneously, water played an important part in the Roman-Byzantine and Ottoman cultures. Therefore, emperors, sultans and other important people alike after Constantine took great care in maintaining and restoring waterworks. They also hired talented architects and craftsmen to realise these projects.

Two key figures connected to the history of Istanbul’s water supply: emperor Valens (left), who completed the new high-level waterway, and Mimar Sinan (right), the architect responsible for major expansions of the Ottoman waterway. Source: Münzkabinett Berlin (left) and Wikimedia Commons (right).

Generally, you can still find installations that made use of the water supply (such as baths, churches/mosques and fountains) in Istanbul, or constructions that were part of it (such as aqueduct bridges and cisterns/reservoirs). Besides physical traces of Istanbul’s water heritage, there are also intangible aspects, namely people and institutions that are connected to Istanbul’s water supply.

During late antiquity, the water infrastructure was expanded to meet the higher demand and to deliver water to the higher regions. Under Valens (r. 364-378), a second waterway – the Valens Waterway – was completed. The emperors of the 5th century added a channel all the way from Vize near the Bulgarian border, earning the newly expanded system the name ‘the longest Roman water supply’. The system was equipped with aqueduct bridges (like Bozdoğan Kemeri) to cross valleys, and the water was collected and stored in reservoirs both above and underground. What did people use the water for? From Roman times, baths (like the one near Kalenderhane mosque) were already considered a standard commodity for any well-equipped city. Even though water usage was heavily regulated, luxurious commodities like these baths drastically increased the demand for water. In the Byzantine period, water also remained an important part in cultural religious terms. Churches were sometimes built atop a cistern, or they contained a fountain or a holy spring (like Panaya Elpidia church’s dedicated to St George in Kumkapı).

The Ottomans made great work of refurbishing the existing water infrastructure to provide their growing capital with freshwater. This renovation, starting with Mehmet II’s (r. 1451-1483) refurbishment of the Hadrian Waterway, culminated with the expansions of the water infrastructure under Süleyman’s chief architect Mimar Sinan (c. 1488/1490-1588). The Ottoman water supply increasingly went underground through an intricate pipe system, and newly added channels joined with others in water distribution chambers (i.e. Tezgahçılar taksim). This enabled engineers to concentrate and direct water from different sources to different parts of the city. Furthermore, the water pressure was regulated through water towers (su terazisi, as seen near the Şehzade complex).

The Ottoman water system is known as Kırkçeşme, named after the forty fountains that were installed by Mehmet. The new system supplied different types of installations. Like the Romans, bathing played an important role in Ottoman culture. Bathhouses, or hamams (like the Bayezid and Çinili hamams), were important places to relax, gossip, and even to plan a rebellion. There are plenty of hamams in Istanbul – some are in use, others simply exist as ruins. Culturally, water was deemed an important part of daily life, and it was made available through public fountains (Ayşe Sultan’s Fountain and the Şehzade mosque courtyard fountain) and other distribution points such as water kiosks (sebil, sometimes accompanied by a fountain).

Not all water heritage is tangible, such as the stories about the people that were involved with Istanbul’s water. This includes the water-carriers (sakalar) that distributed water on the streets, or the fire brigades that combated regular fires in the city as many buildings were made out of wood. Neighbourhoods near the coast, such as Kumkapı, hosted communities for whom water was significant, such as the Armenian fishermen.

KarDes Water Heritage Tour: the historical in the present

Even though the water supply was a practical problem, water increasingly also gained cultural value in the city of Istanbul. Today, if you look closely, you can see remnants of the historical water supply scattered throughout the city. This includes parts of the infrastructure and the stories surrounding the people that dealt with Istanbul’s water supply.

Curious? You can either walk through Istanbul with an online guide or you can explore the tour from the comfort of your couch in the KarDes app.