By Esen Kayan

At this moment we feel the weight of the increasingly looming climate change, especially in bustling cities where people are concerned that the sources of life we consume on a daily basis may not be sufficient for all of us. In Istanbul, people strive to raise awareness to the water crisis we’re facing, as the city has never been more densely populated than before. Observing the situation Istanbul is now in, scholars analysed the water heritage in Istanbul to guide them through the current water crisis in the city.

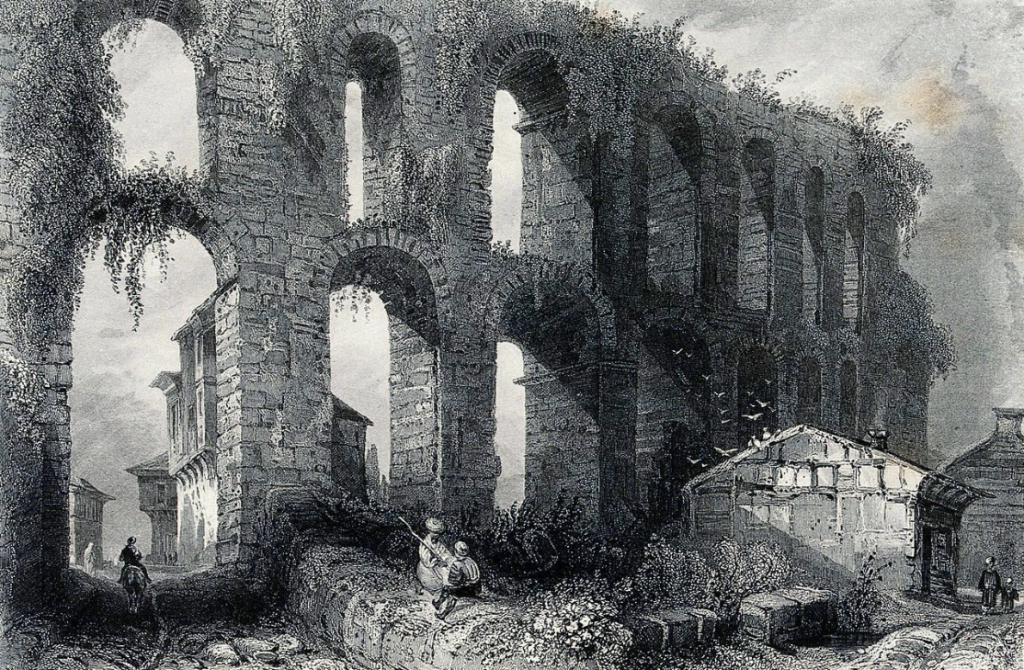

You have probably seen the Valens Aqueduct if you have been to Istanbul and went through the traffic around the Fatih region and the historical peninsula. But what you don’t know is that today, the Valens Aqueduct can be more than just a neglected ancient ruin we pass through in our sedentary life. The monument has been altered, changed, and transformed over a millennium, during which it was always physically and spiritually connected to Istanbul. Looking through its past uses, many scholars in archaeological, cultural heritage, architectural and urban planning studies investigated how the water heritage predecessors of Istanbul established can be beneficial for the next generations to come.

As a part of the NIT Urban Heritage Lab 2022, the proposals for the revalorisation of the Valens Aqueduct include not only environmentally conscious urban sustainability policies but also preservation, which will strengthen our understanding of our surroundings. The projects involve cultural heritage innovations that evoke a sense of belonging to the city and a sense of connection to our ancestors of centuries ago who had similar concerns. The publication is edited by Mariëtte Verhoeven, Fokke Gerritsen, Aysel Arslan, Alvise Cecchetti, and Özgün Özçakır.

My duty is to address what the projects are promising to us – the locals of Istanbul, and to introduce the notion of water heritage to you.

The History of the Valens Aqueduct

Two centuries before Constantinople was the capital of the Roman Empire, a water supply line in Istanbul was constructed under the rule of Emperor Hadrian (r.117-138 AD). The source of this Hadrianic Line was springs located at Cebeciköy. Emperor Constantine then initiated the building of a new water supply line with his son Constantius (r. 337-361). The new line was completed under the reign of Emperor Flavius Julius Valens (r.364-378) in 373 AD by the prefect Clearchus. Named after the emperor Valens, the Valens Water Supply System brought water to Constantinople from Thrace, and the Valens Aqueduct was the final point at the heart of the metropolis. The source of the Valens Line (in Turkish Bozdoğan Kemeri) is located at the springs of Danamandıra and Pınarca.

The Valens Aqueduct, on its own, helped supply for the increasing population of the Roman Empire and consequently to the expansion of the empire. Thus, it was considered a remarkable architectural innovation that was continuously renovated and used by its successors. PhD candidate Jip Barreveld from Leiden University states that ‘enabling the comforts of Roman urbanism, aqueducts were not only marvels of engineering but also effective means of imperial propaganda.’ Nearly three times longer than the known length of any Roman water supply2, the Valens line was named ‘the longest Roman water supply line’ by Kazım Çeçen. The water collected in open cisterns was used for agricultural purposes. The underground cisterns – including the famous 1500-year-old Basilica Cistern – supplied drinking water. If not for the Valens Aqueduct, Istanbul today might not have been the exceptionally captivating city that hosted three empires.

Access to freshwater has an immense strategic role, after all it is the essential source to sustain life. Cutting the water supply of a city was a common tactic in medieval siege warfare3, thus the Valens Aqueduct played a very strategic role for the besiegers of Constantinople. During the Avar siege of Constantinople from Thrace in 626, the Avars attempted to capture the city via the land walls, and cut the Valens water line. Despite this, it is speculated that the water in the city was supplied through the Hadrianic line, until Emperor Constantine V (r.741-775) ordered the restoration of the Valens line in 766.

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, Mehmet II the Conqueror (r. 1451-1481) ordered the restoration and maintenance of the aqueduct. Mehmet II also built a group of public fountains called Kırkçeşme (forty fountains), and in the 16th Century, Sinan, the Architect, extended the Kırkçeşme water supply line.

Once regarded as the greatest architectural project in the world and quite an expensive initiative at the time, the Valens Aqueduct is now overshadowed when other historical areas in Istanbul are at the forefront. To assess the contemporary appreciation of the Valens Aqueduct, a survey was conducted to find out people’s perceptions of the Aqueduct. The results have shown that the respondents want to know more about the aqueduct and the water heritage that was left behind by people of the past.

”A monument I have loved to walk under since childhood, it feels like a gateway to old Istanbul.”

Female respondent, 36-50 years old, lives in Istanbul.

”For a short period, I had to go through these arches to go to my sister’s home. Whenever I did this, I felt like I was going to a special part of Istanbul. As if I was crossing a boundary.”

Female respondent, 18-35 years old, lives abroad.

”I walked on top of it, it is very dangerous, but I love it very much!”

Male respondent, 36-50 years old, lives in Istanbul.

Below, we present ideas on how to re-experience the Valens Aqueduct and appreciate the water heritage as the Romans, the Byzantines, and the Ottomans did while maintaining and preserving the landscape and assessing the needs of people and today’s climate.

Project Proposals

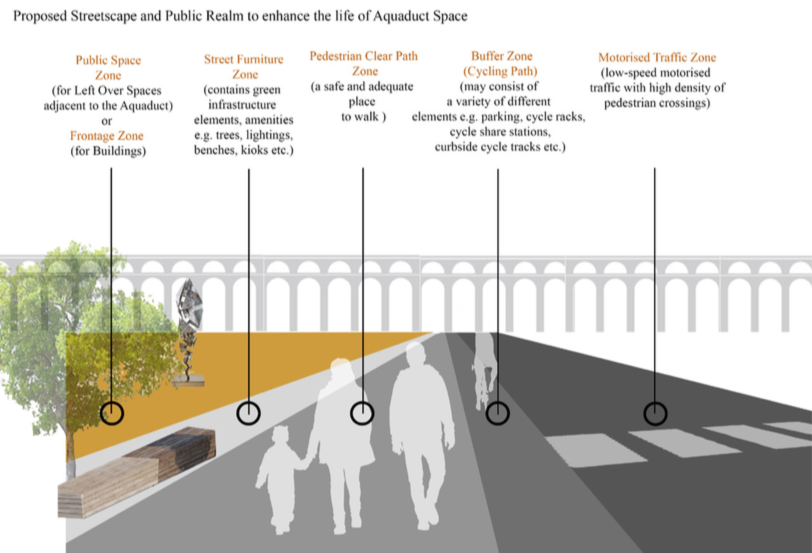

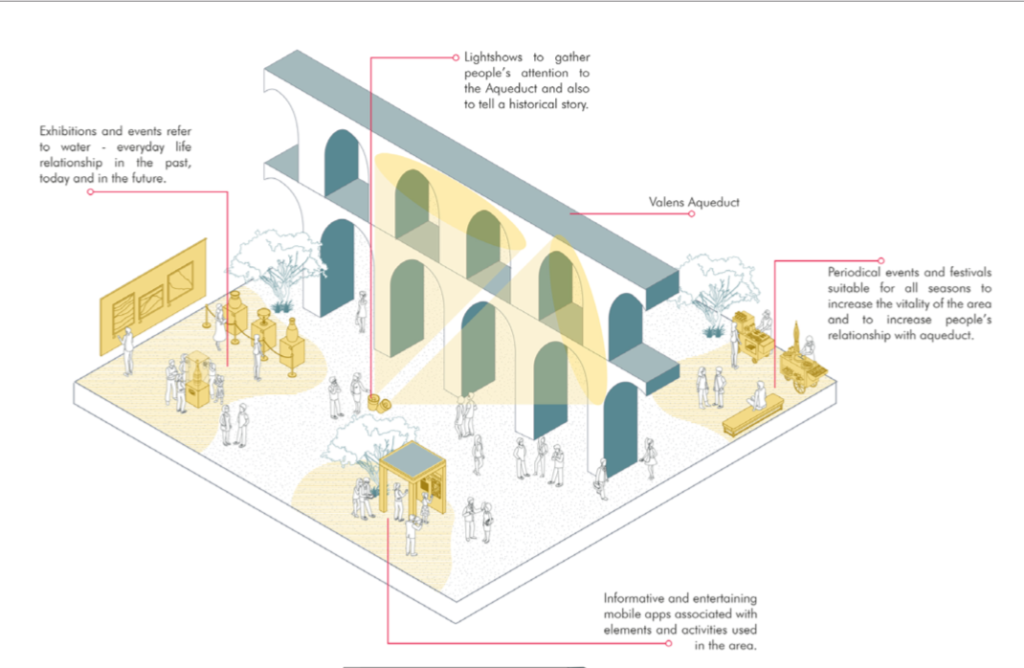

Pursuing Water through a Historical and Permeable Ecological Corridor. An Open-Air Museum Concept

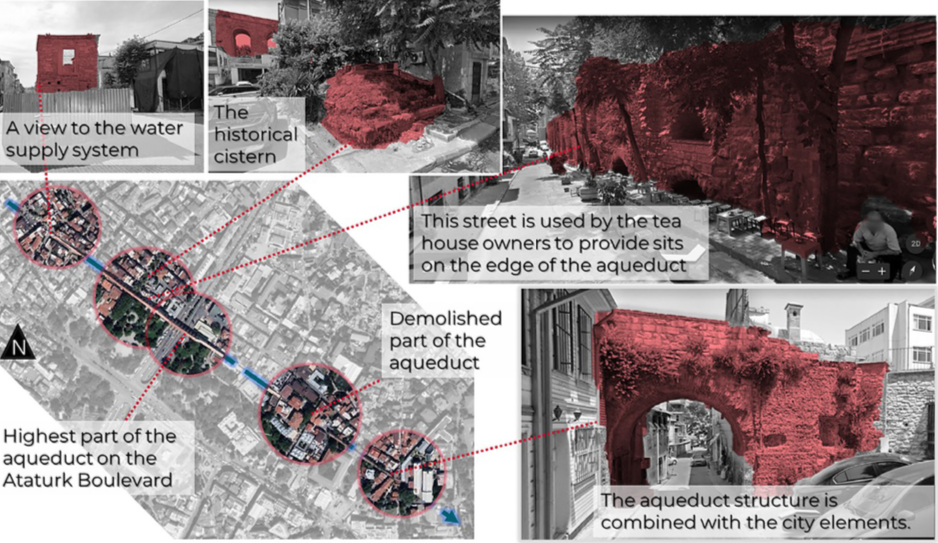

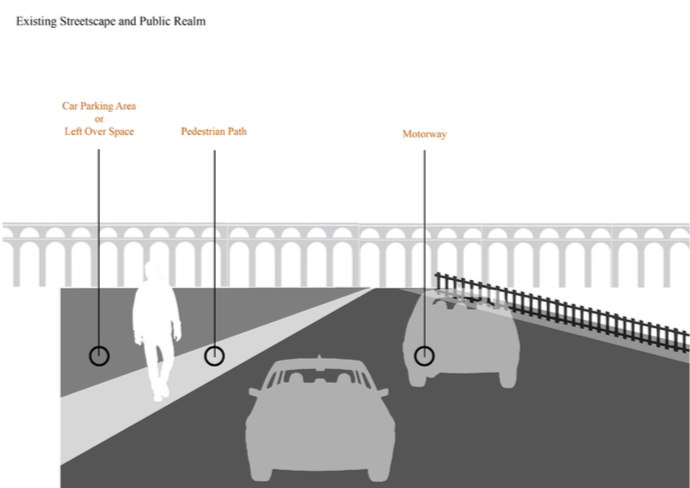

The project aims not only to integrate historical urban fabric to contemporary life, but also to promote sustainable land and water use. First, the project members Alvise Cecchetti, Beste Nur İskender, Gamze Özmertyurt, Merve Okkalı Alsavada, and Müge Yaylacık took a field trip to assess the surroundings of the Valens Aqueduct. Their findings showed that there is limited pedestrian access, heavy traffic volume and traffic noise, car-oriented urban mobility, and no qualified green areas.

To integrate history into contemporary life, they introduced an open-air museum concept. By assessing the movement patterns, the proposal members designed an ”ecological corridor” with a pedestrian area. In line with the theme of water heritage, the project’s aim also includes water recycling. It must be noted that re-use does not refer to connecting the grandiose monument to modern pipes and pumps. Still, a rainwater collection system will be incorporated to recycle our resources and create new cycling narratives for water. Urban gardens and parks with a choice of rain-attracting plants and rainwater ponds could be incorporated as a part of the green infrastructure.

The revitalisation of the Valens Aqueduct thereby not only celebrates the cultural heritage of the city but also functions as a tool to help raise awareness over re-cycling, environmentalism and the water crisis.

Some Activities Included in The Open-Air Museum Concept

Re-conceiving the Source of Life of the City Through Intervention – Intersection – Interaction – Integration

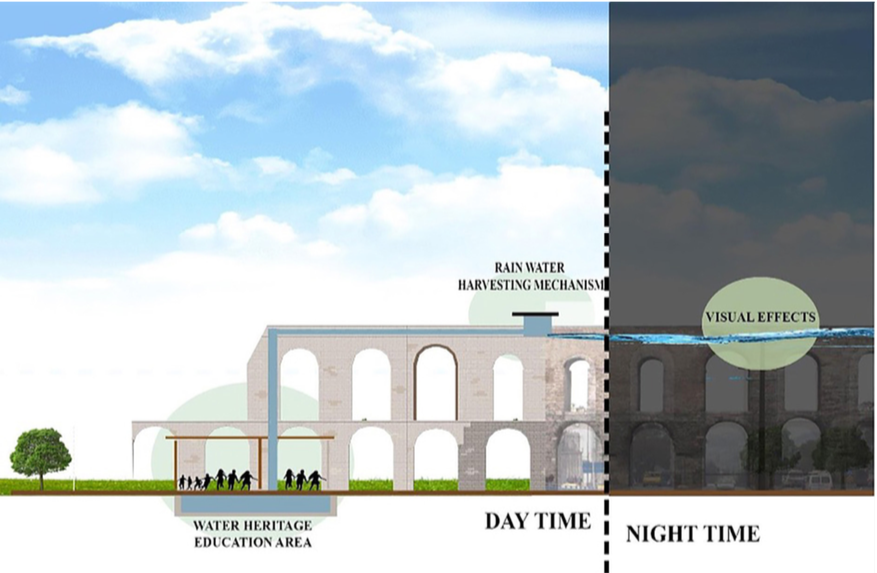

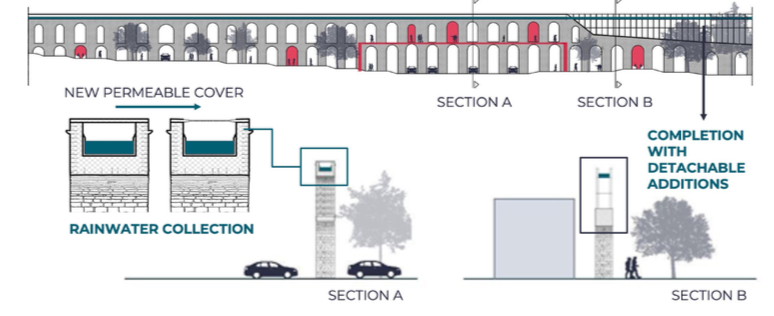

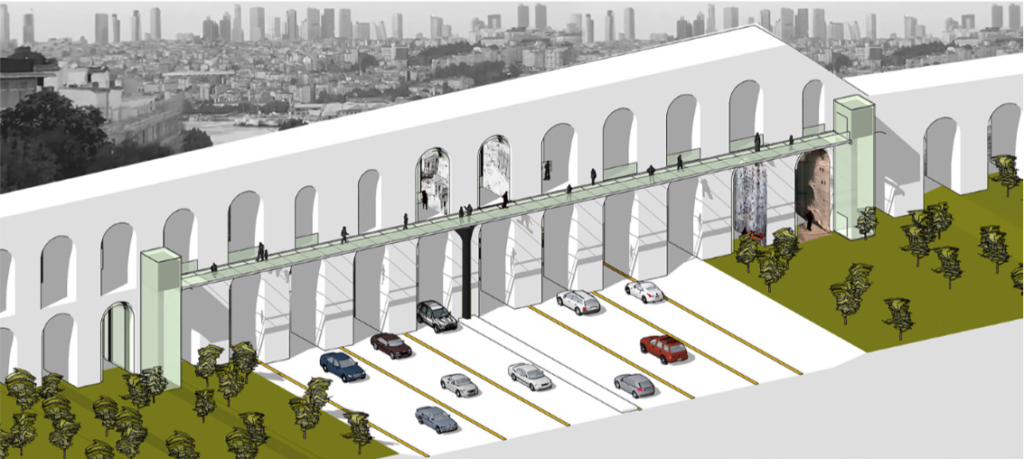

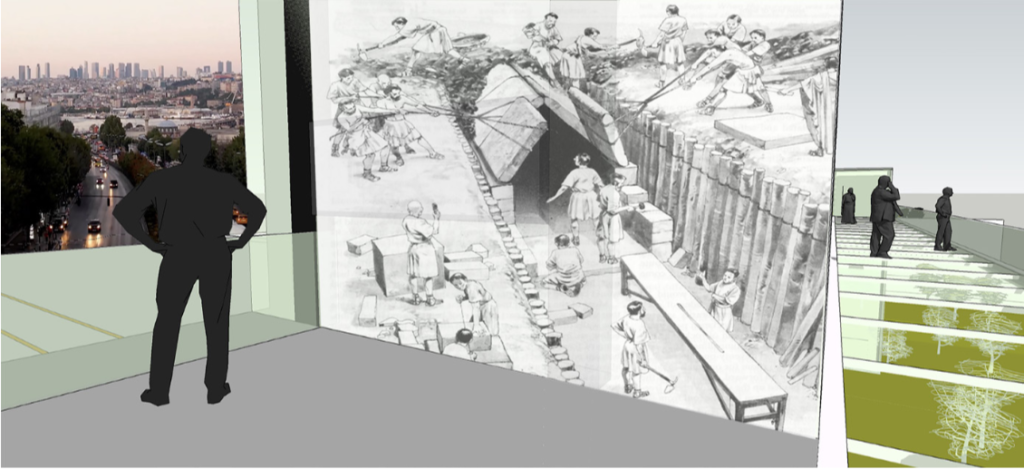

To reconnect the water network with urban life, the project members Zeynep Akgül, Nihan Bulut, Öykü Çömez, Eser Epözdemir, and İdil Ece Şener propose adding additional constructions while not disturbing the Aqueduct itself. To revitalise the neglected Aqueduct, a pedestrian over-pass would be designed to increase communal engagement as a bridge to connect the Saraçhane and Fatih parks.

The need for a pedestrian over-pass was realised after investigating the challenges that needed to be confronted, such as restricted access, inclusivity gaps and urban expansion. The over-pass will help people be educated about the purpose of aqueducts, their mechanics and historical significance. As a result, the project will strengthen the societal cohesion of its surroundings. Adding elevators on both sides will help anyone with any physical condition travel on the over-pass.

To utilise the Aqueduct in the context of water re-cycling, the project members planned to add a rainwater harvesting function with an elevation system. The system will be visible to ensure the transparency of the process. The project members also stressed the importance of not damaging the aqueduct, so they proposed interventions that are detachable/reversible, and that will not dominate the structure.

Figure 7: The elevation drawing by Temiz, G. (2019), edited by the author.

Proposal for designing an over- pass near the Valens Aqueduct

Modules designed to inform the public and raise awareness of water heritage

The Valens Aqueduct as an Urban Living Lab: Integrating Networks, Enhancing Interfaces, and Revealing the Identity

To create an Urban Living Lab surrounding the Valens Aqueduct and the historical peninsula, project members Cem Almurat, Gökhan Okumuş, Itminan Tasneea, Özge Özeke Eski and Sıla Akman Aşık came up with three proposals. The proposals aim to collaborate and improve networks between stakeholders, policymakers, and relevant authorities in Istanbul. The open labs will introduce new technologies, such as applications that monitor rainwater and greywater harvesting, water footprint, and water purification in the city.

Urban Living Lab model for the Valens Aqueduct and its surroundings

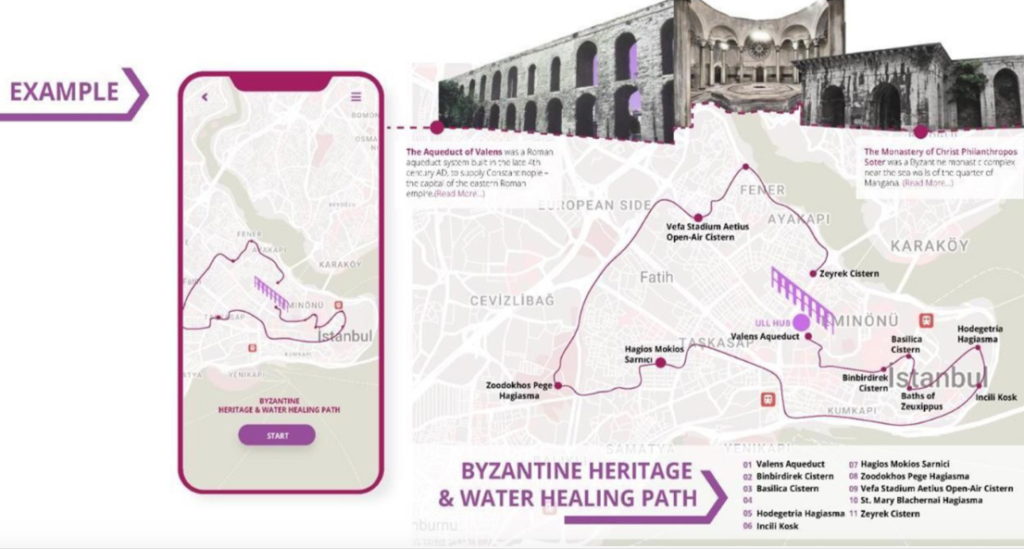

The creators of Urban Living Lab first propose Saraçhane and Fatih Parks as the core of the lab, also including Women’s Bazaar and Archaeopark. Workshops and learning activities focusing on urban sustainability, cultural heritage, and water heritage will take place in the open-lab. The second proposal of the Living lab is to launch the WALK APP. For citizens and tourists, WALK APP connects the Aqueduct with people’s walking excursions in the historical peninsula, which will help to decrease carbon footprint. The WALK APP can also be merged with existing apps such as Yürü Be İstanbul by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IBB), Kardes, Sweatcoin, which rewards cryptocurrency for walking, or CharityMiles, to use walking miles as a donation. Lastly, the creators proposed that Valens Aqueduct be maintained as a monument. As a result of the survey, locals love walking on top of it to enjoy the view of Istanbul. The members decided to design a promenade on top of the Aqueduct.

“Byzantine Heritage and Healing Path” – A prototype walking path designed in ULL

Field of Flowing Memory: Bringing Water Back to the City

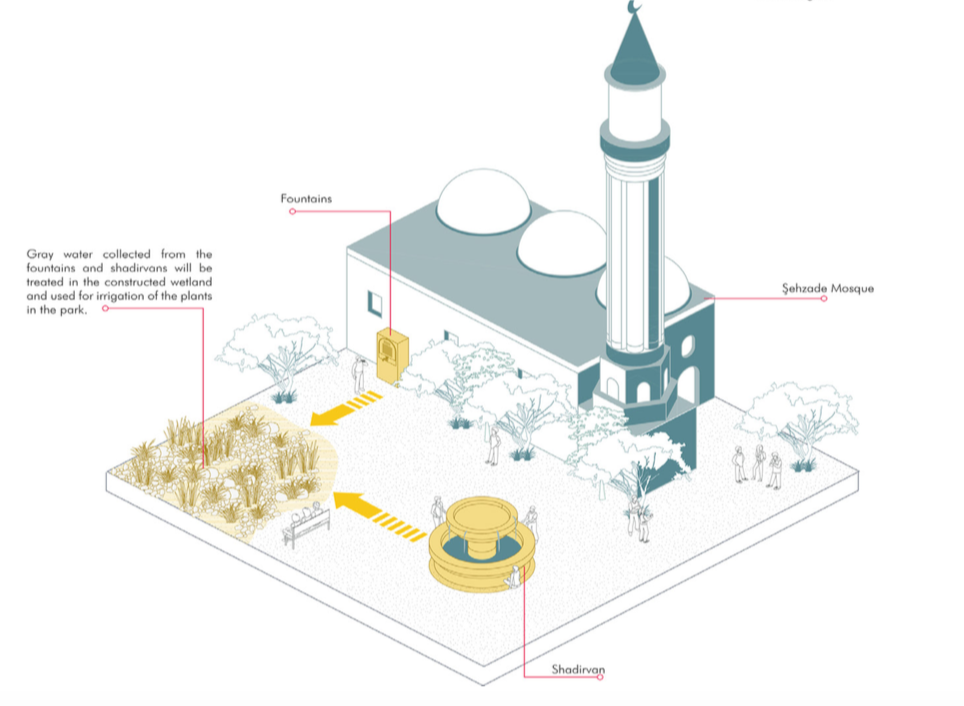

Dilara Ayşegül Kökten, Gökçen Özalp, Sunay Paşaoğlu, Imke Seising and Tuğçe Sözer questioned how to bring water back to the city, as the relationship between the Aqueduct, water and the people is currently broken due to modern interventions. The members analysed the water dynamics of the area, and urban evolution to bring water where it used to belong.

The project members focused on water as the primary theme of the project and historical evolution as a guiding factor. The project aims to tackle the main problems of scarcity and urban flooding through water-sensitive urban design. The project moves with a holistic approach in macro, meso, and micro scales. To do so, the themes are considered in all decisions and stages.

Water-sensitive urban design involves water catchment, treatment, and storage elements, including bioswales, constructed wetlands, detention basins, and septic tanks. Overall, the proposal integrates water in every aspect and simultaneously preserves Byzantine heritage through telling the story of Istanbul in the past.

Water Related Decisions: Water Related Zone

Cultural Axis

Comment down below which inspiring project you would like to see become actualised in the future. The publication is available on the NIT website.

Cover photo:

Wikimedia Foundation. (2024, January 20). Aqueduct of Valens. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aqueduct_of_Valens

Bibliography:

Arslan, A., Cecchetti, A., Gerritsen, F., Özçakır, Ö., Verhoeven, M. (Eds.)(2023). Water Heritage for Sustainable Cities, Proposals for Revalorization of the Valens Aqueduct in Istanbul. Netherlands Institute in Turkey

Barreveld, J. (2021, June 11). Aqueduct Warfare: Water Infrastructure and Sieges in Post-Roman Europe. Leiden Medievalists Blog.

Valens Aqueduct. Istanbul Tour Studio – Istanbul Guide. (n.d.). https://istanbultourstudio.com/things-to-do/valens-aqueduct

Footnotes:

- Wikimedia Foundation. (2024, January 20). Aqueduct of Valens. Wikipedia. ↩︎

- Valens Aqueduct. Istanbul Tour Studio – Istanbul Guide. (n.d.). https://istanbultourstudio.com/things-to-do/valens-aqueduct ↩︎

- Barreveld, J. (2021, June 11). Aqueduct Warfare: Water Infrastructure and Sieges in Post-Roman Europe. Leiden Medievalists Blog. ↩︎